Table of Contents

ToggleOur faces are becoming digital keys. They unlock phones, let us board planes, and grant us access to secure spaces. Facial recognition is fast becoming central to how we prove who we are in the digital age.

But there’s a hidden twist: modern systems don’t just recognize identity—they can also infer emotions. A smile, a frown, or a tense jaw can all be classified into categories like “happy,” “angry,” or “nervous.” For humans, these signals are fleeting and often ambiguous. For machines, they risk becoming permanent data points, stored and analyzed without context.

That’s where the work of Dr. Alejandro Peña—PhD in Deep Learning and Responsible AI, Telecom Engineer, and member of the research team at Identy.io—comes in. In 2020, together with colleagues at Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and MIT, he asked a provocative question: Can we build face recognition systems that identify people while ignoring emotions?

The Core Idea: “Emotion-Blinded” Recognition

Most facial recognition systems are trained to identify people. Yet, unintentionally, they also capture hidden traces of our emotional state. That means a system designed to let you unlock your phone could, in theory, also detect that you are tired or stressed.

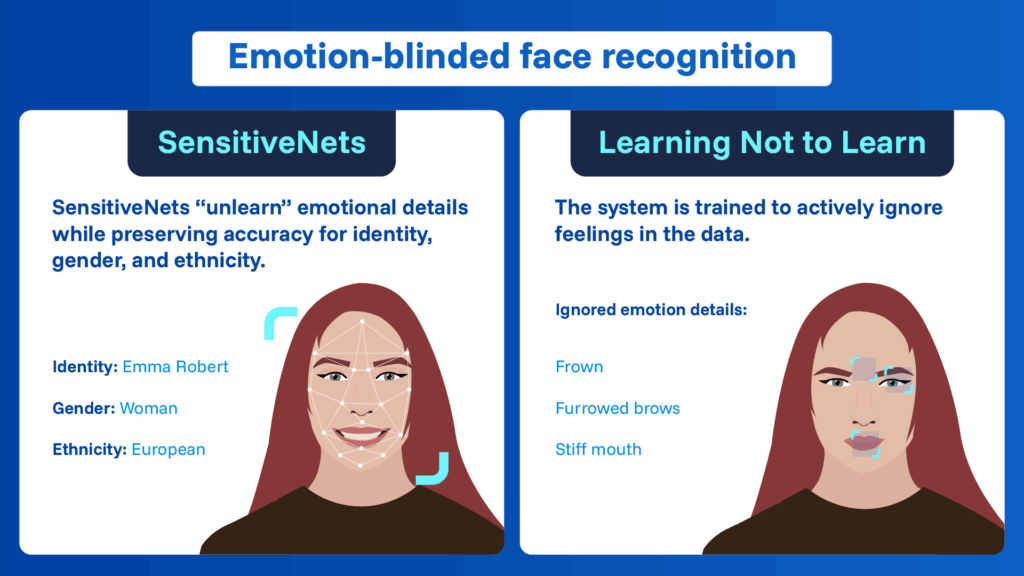

Peña’s team explored whether identity verification could remain accurate if emotional information was stripped away. They tested two approaches:

- SensitiveNets: Imagine teaching a student to focus only on names in a class photo and ignore everything else.SensitiveNets “unlearn” emotional details while preserving accuracy for identity, gender, and ethnicity.

- Learning Not to Learn: This approach is like giving a student a penalty every time they pay attention to emotions instead of identity. The system is trained to actively ignore feelings in the data.

The results were clear: systems retained high accuracy (over 95%) for identity verification, gender, and ethnicity—but their ability to detect emotions dropped by more than 40%. This proved that privacy can be designed into AI by excluding unnecessary and sensitive details.

Why This Matters: Real-World Risks

At first glance, machines reading emotions might sound useful. But once tied to identity, the risks become serious.

- Workplace Monitoring: Imagine cameras evaluating employees’ “motivation.” A neutral expression could be mistaken for disinterest, influencing performance reviews unfairly

- Education: AI in classrooms might measure “engagement.” Students who process information quietly could be penalized for not “looking attentive.”

- Security: A nervous traveler at an airport—perhaps simply afraid of flying—might be flagged as “suspicious” by emotional AI.

- Marketing: Billboards could scan passersby and adapt ads based on mood. A sad face might trigger ads for comfort food or quick fixes, without the person realizing their emotions were exploited.

- Healthcare and Insurance: Emotional data could be used to make assumptions about a patient’s mental health or lifestyle, potentially affecting coverage or employment opportunities.

These examples show how emotional data, if misused, can reinforce bias, manipulate behavior, or invade privacy.

A Historical Parallel: Fingerprints vs. Emotions

When fingerprints became standard for identification in the early 20th century, they revolutionized security. They are unique and stable, but they don’t reveal private details about personality or mood. They serve one purpose: verifying identity.

Facial expressions are different. They change constantly, vary across cultures, and can be misinterpreted. A smile might mean happiness, politeness, or even discomfort. Treating such signals as hard data risks oversimplifying complex human realities.

Peña’s work argues for keeping face recognition closer to fingerprints: focused on stable identity, not transient emotions.

Beyond Privacy: Ensuring Fairness

The study also revealed how emotional cues can introduce bias. In one experiment, systems trained to rate “attractiveness” favored smiling faces. Smiles were incorrectly treated as indicators of beauty, giving certain expressions an unfair advantage.

By removing emotional data from the equation, the researchers reduced these biases and moved closer to equal treatment across individuals. This shows that protecting privacy is not just about secrecy—it is also about fairer outcomes.

From Research to Real-World Relevance

For digital identity to succeed globally, it must be trusted. That trust depends on boundaries: verifying identity should not mean exposing emotional states. By proving that it’s possible to blind systems to emotions without losing accuracy, Peña’s research offers a blueprint for more responsible AI.

This aligns with Identy.io’s core values:

- Privacy first – ensuring identity verification doesn’t expose unnecessary details.

- Fairness – designing systems that work equally well across cultures and groups.

- Inclusivity – building technology that empowers, rather than discriminates.

Conclusion

As artificial intelligence advances, the critical question is no longer just what can machines do? but what should they do?

Dr. Alejandro Peña’s work demonstrates that it is possible to design face recognition that verifies identity while leaving emotions out of the equation. This not only safeguards privacy but also promotes fairness and trust. Our faces may be public, but our feelings are personal—and technology must learn to respect that line.

Read the full research paper here: https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.08704 Biometric fingerprint identity control

References

- ISO/IEC 24745:2011 – Biometric Information Protection

- EU GDPR Article 9 – Special Categories of Personal Data

- European Commission – Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI (2019)

- NIST – NIST Special Publication 800-63-3 – Digital Identity Guidelines.